The following mini essay is kind of the throughput from my old blog. It was originally posted there over four years ago in three installments. As it was sort of going in the direction that I want this new blog to go, and since I want a test post to kick things off, I’ve decided to repost it here. Originally I was thinking of revising and expanding it, but instead I think I’ll leave it pretty much as is — I’ve updated the wording a bit to account for the fact that it was written a few years ago and I’ve added a few explanatory footnotes. Do feel free to let me know in the comments what you think of the format and style, as this may affect how I continue in this blog.1

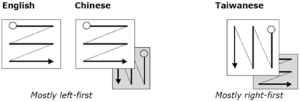

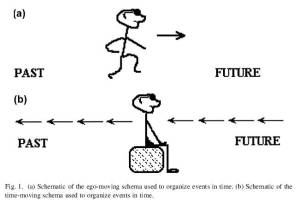

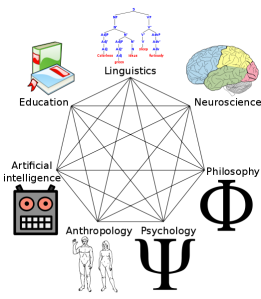

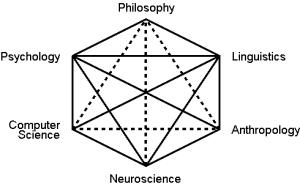

One last note about the background of some of the ideas expressed here: I’m writing about metaphor, not simply as a literary ornament, but as a way of thinking about the world. This is a much discussed topic of late, especially in the field of cognitive linguistics (a subject I’ll write much more about in future posts). We make sense of the world around us by thinking about it in terms of metaphor. This is something we begin to do from infancy. When a baby spends hours putting a block in a box, taking it out, and repeating these actions endlessly, he is constructing a mental schema of inside and outside, of a container. We later apply this schema to many things in our language and the world around us. When we say we are “in trouble” we are conceiving of “trouble” as a container. This is a metaphor. The centrality of metaphor to our language and our cognition is explored in the groundbreaking book Metaphors We Live By (1980), by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. I’ll probably post more on this topic myself later.

Interestingly, the idea of fundamental cultural metaphors was explored earlier by Ernst Robert Curtius in European Literature of the Latin Middle Ages (1948). I first encountered Curtius while writing my doctoral dissertation, and, after constructing the appropriate footnotes, filed him away as something I should come back to later. Well, Curtius and the book by Lakoff and Johnson mentioned in the previous paragraph are occupying my thoughts in particular these days, so you’ll probably hear more about them later too.

One last point, several of the images below are taken from this excellent website on Ancient Sailing and Navigation, which also has an excellently detailed discussion of the history of these techniques and technologies, so do click on through if you’re interested.

And now the original post...

I’ve become interested in the relationship between science and technology on the one hand, and literature and culture on the other, and I’ve been working this into my lectures a bit.2 Here’s an example of a kind of neat idea I came up with for one of my classes. First a little background:

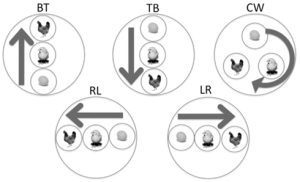

One courses I taught a few years ago was called Narrative. There weren’t many stipulations for this course other than that we were to consider narrative from fairly broad terms. I was quite excited at the prospect of teaching this course, since my own research was moving in this direction, what with my work on discourse analysis and pragmatics,1 and having recently given a paper at the Narrative Matters conference I was full of ideas. I decided to divide the course into two parts. First we would survey the major narrative genres of western literature — myth, folktale, legend, etc.; epic and saga; romance; the novel; the short story — and then we’d spend the rest of our time on thematic units. I wanted to consider narrative broadly speaking as a way human beings tend to organise information and make sense of their world. Starting off with myth was a particularly good way of introducing this idea. We compared parallel stories such as creation myths, destruction myths (like flood myths), and so forth from the Bible, Greek myth, and Norse myth. This also gave us the opportunity to do a bit of comparative mythology and consider the differences in religious beliefs and some of the different world views these reflect, for instance the very personal relationship between humans and God in the Judeo-Christian world and the relationship based on fear in the Greco-Roman world.

I also wanted to spend some time on some of the fundamental narratives of western culture, and the first thematic unit that I settled on was travel and exploration. As I was prepping my lectures on this topic it occurred to me that there was an interesting parallel pattern between the travel and exploration literature and the world views reflected by this imagery on the one hand, and the development of sailing technology on the other. I suggested to the class that the travel and exploration metaphor could be seen as reflective of cultural change from the ancient world to the modern. This narrative metaphor often describes man’s relation to the world in which he lives — the narrative is symbolic of man’s place in the universe. And the use of this narrative metaphor changes over time to reflect different beliefs about man’s place in the world.

In the Odyssey, one of the oldest recorded travel narratives in western literature, we see human beings at the mercy of the elements, and by extension the gods. Odysseus and his crew are constantly driven about against their will by the elements. And as we had already discussed in our mythology section, this reflects a common idea in Greek mythology that humans are at the mercy of capricious gods, a common Greek view of man’s place in the universe. This of course is entirely consistent with ancient sailing technology. The ancients had square sails. Here’s a picture of a square sail:

Ships with square sails are not very manoeuvrable. Essentially you go in the direction that the wind blows you. If the wind was blowing the wrong way, you were out of luck, so you’d have to wait for a favourable wind. Sure, you had oars to row, but that wouldn’t take you very fast or very far. If a storm blew up, you’d use the oars to row quickly to shore, as happens at one point in the Odyssey. Thus sailors were at the mercy of the wind, hence the sense of helplessness in the Odyssey.

As a side note, it’s interesting to compare the attitudes towards sea travel in Homer and in Virgil. While Odysseus is certainly trying to get home, he appreciates his journey and learns many things along the way. Aeneas, on the other hand, is much more focussed on the final destination. While the Greeks were a seafaring culture who lived on a peninsula with many small islands and relied on sea travel for their economy, the Romans were a much more land-based culture who hated and feared the sea, though they were practical enough to become proficient at it when required to do so.

It’s also interesting to see what later writers did with the Homeric story of Odysseus. The same story has three different meanings for Homer, Dante, and Tennyson. Homer’s Odysseus is simply at the mercy of the gods. While he does take some interest in the things he sees along the way, his journey is not his will — in fact he’s against it. His journey and his life is determined by the Fates and the prophecies about what will happen to him. In the Greek mythological world, man can’t control his own fate. In the Divine Comedy, in contrast, Dante places Ulysses in hell. For Dante, Ulysses journey was an act of will — Dante wasn’t familiar with Homer first hand. From Dante’s Christian viewpoint willfulness is sinfulness. Man shouldn’t try to control his own fate, as that was up to God. And finally, for Tennyson, in his poem “Ulysses”, the hero’s journey is also an act of will, but it is more positive. Tennyson exalts his purposefulness and striving. Man should try to control his own fate. Thus for Dante sailing out into the ocean is bad and Ulysses is placed in hell for it, but for Tennyson it is good and he is lionised for it.

But back-tracking to the middle ages for a moment, with relatively little advance in sailing technology over the ancient world, we can see a similar metaphor, only the characterisation is different in the Christian world view. For instance, in the Old English elegies “The Wanderer” and “The Seafarer” harsh exile is pictured in terms of a lonely journey in a boat, and the homiletic implication of this exile/pilgrimage is that the Christian soul’s ultimate destination is back to God. God is the only course to steer towards. Similarly, in the later middle ages, in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in the Man of Law’s Tale, Custance, who is set adrift at sea by her antagonists to get rid of her, puts her faith in God: “In hym triste I, and in his mooder deere, / That is to me my seyl and eek my steere”. God is her sail and her rudder, her means of propulsion and steering. Again, this is a metaphor of the relationship between the Christian soul and God, and therefore of man’s place in the world. Though as in the ancient world, man does not control his fate, it is not a capricious god to whom he is subject.

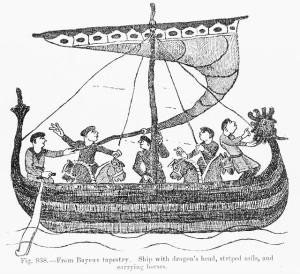

Known as great sailors in the earlier part of the middle ages, the Vikings, who really only had the square sail, cheated a bit by lowering one end of the sail to allow for greater manoeuverability. But for the most part they made do with very simple means and no sophisticated navigational equipment.4 Here’s a picture of a Norse knarr:

They were often blown off course, and as described in the Vinland Sagas, it was often due to accident that they made discoveries such as Greenland and Vinland. Interestingly, there’s quite the mix of chance, fate, luck both good and bad, pagan, and Christian in the Vinland Sagas.

As for the advance in sailing technology, in the late middle ages or early renaissance, the triangular lateen sail began to be used in Europe. Here’s a picture of a lateen sail:

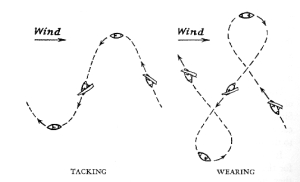

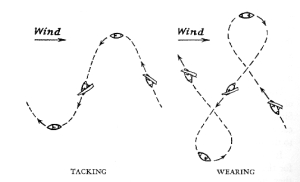

The triangular sail, of course, works like a wing — high pressure on one side and low pressure on the other — and it allows a ship to sail almost directly into a headwind. And so by tacking in a zigzag pattern ships can sail go in any direction and are no longer at the mercy of the wind, as long as there is wind, as seen here:

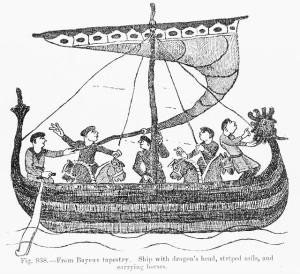

(You can read a good explanation of all this here.) Ships also started using sternpost rudders rather than steering with an oar hanging off the right side (starboard, literally the steering side, as opposed to the left side called port which was the side towards the dock, also known as larboard or loading side). The stern mounted rudder made it possible to steer larger ships, and larger ships could carry more provisions, including most importantly fresh water. These along with the old square sail (to take efficient advantage of favourable winds), as well as improvements to navigational technology allowed for real exploration to begin at the end of the middle ages and throughout the renaissance, kicking off the European age of discovery. Here’s a picture of the complete package:

Note both the square sails and the triangular lateen sail.5

These advances too are reflected in the imaginative literature of the period. This is of course the age of humanism, when the cultural focus shifted from the purely religious to the world of man. People began to define their place in the world in terms other than purely spiritual ones. The eighteenth century, for instance, is full of travel literature, perhaps most famously Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Gulliver goes out into the world ostensibly to discover things about other people and places, but in fact learns about his own country in the process. Mankind defines itself through its exploration of the outside world, through its own ability to direct its own course in the world. This is a radical shift from the medieval seagoing metaphor as demonstrated most clearly in Chaucer’s Custance, who is really only defined by her relationship to God. The humanist shift in cultural focus goes hand in hand with the seagoing technological shift.

Though Gulliver can sail anywhere in the world, sailing is still a risky business and he is frequently stranded. Both Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and the outer frame narrative of Walton’s arctic exploration in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein sound a note of danger in unbridled exploration. This is perhaps somewhat comparable to Dante’s perspective of Ulysses. While mankind is more and more able to govern his own destiny, there are some things he shouldn’t meddle with. If the sea voyage is a metaphor for man’s place in the world and man’s relationship with God, then trying to control your own destiny rather than following God’s guidance is a problem.

With the 19th century we enter the modern era, and the biggest technological advance which changed seagoing was the steam engine. Suddenly ships were no longer dependent on wind at all. Even if there wasn’t any wind, a steamship could still go. The technological progression of the square sail to the triangular sail is completed with the advent of the steam engine. This is dramatically demonstrated in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, in which just such an incident happens. When the winds die down, the steam engines are fired up, and at one point Phileas Fogg nearly burns up the ship itself in an attempt to win his race against time. This is the ultimate expression of man’s desire to control his own fate. Fogg overcomes all obstacles thrown in his way in order to win the bet, and that includes the obstacles of the natural world and the elements. This is reflected of the Victorian elevation of man’s ability to control his world. In this world-view man has a special place in the world, he is at its pinnacle. He even sought to have mastery over nature — nature was something to be tamed or controlled. And it is in the late 19th century that science is really beginning to challenge religion, with the realisation that the geological age of the earth is vastly longer than the Bible accounts for, and Darwin’s evolutionary theory challenges the Biblical creation story. The Victorian man did not adapt to his surroundings, he adapted the surroundings to suit himself, and this is subtly commented upon in Verne’s novel with the description of the British Empire which sought to impose its customs and organization (often unsuccessfully) upon the world. Furthermore, there is a shift from the age of exploration to an age of tourism. The world has been largely explored by Europeans, and Fogg is really more of a tourist than an explorer. The world is a much smaller place, and this makes man’s stature seem the larger. Instead of defining himself in relation to the world, man redefines the world in his own image.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness stands out as the most striking example of the travel and exploration metaphor. But now, instead of a journey outwards, it is a journey inwards. Instead of defining his place in the world, man is defining himself. Man’s relationship with his world becomes his relationship with his own inner psyche. Man’s attempt to control nature and the world around him becomes his attempt to control human nature and the world within him. But his sense of control is an illusion since he has no real self-control.6 Yet again the metaphor is redefined for a new era which is so self-referential and solipsistic.

And so I leave you with this little bit of obscure though apropos verse which explains the post-colonic part of the title:7

Leave to Heaven, in humble trust,

All you will to do:

But if you would succeed, you must

Paddle your own canoe.

* Yes, a footnote on the title. Let me know what you think of the rampant footnoting: Pretentiously academic? Compellingly non-linear? Just plain annoying? Or for a more amusing musing on the footnote, click here. Or go read Got Medieval’s blog, the locus classicus for footnote humour. As for the note itself, the first part of the title of this post, scip-gefere, is an Old English word which means “A going by ship”. As for the second part of the title, read to the end of the post...

1 This is, I suppose, where the obligatory “Gentle reader” trope would go. Not wanting to follow convention, and yet also wanting to follow convention, I’ve relegated it to a footnote, Gentle Reader. [back]

2 I’m planning a post on scientific approaches to literature and the humanities as well. With all these promises of future posts, I’ll have my work cut out for me. [back]

3 Basically the area of linguistics which looks at contextual meaning. [back]

4 It has been suggested that Vikings navigated by means of polarised light using crystals. See here. [back]

5 I think I remember first learning about all this sailing technology from James Burke’s excellent Connections series. You can see the relevant portion here. [back]

6 The the cognitive psychologists would no doubt point out, we are slaves to our own cognitive processes. Have a look at the blog You Are Not So Smart or the writings of David Eagleman for more on this. [back]

7 Academic titles these days seem to almost invariably follow the formula of the two-part structure connected by a colon. The term post-colonic is a bit of a joke on that. Sorry. [back]