This week we re-open the Endless Knot cocktail bar with the origin of the cocktail Gimlet:

If you haven't seem my previous cocktail videos, by the way, have a look at the cocktail playlist which starts off with the etymology of the word "cocktail" itself. Actually, as far as cocktails go, this one's a twofer, with the classic Gin & Tonic thrown in as well, and even a threefer if you include the Grog. If you want to hear a fuller account of the etymology of the word Grog, have a listen to this episode of the podcast Lexicon Valley, in which the excellent Ben Zimmer explains.

I should also point out, by the way, that though the word gimlet, referring to the small drill, comes into English at least as far back as the 15th century, and the figurative gimlet-eyed goes back to 18th century, the OED doesn't have a citation for the gimlet as a drink any earlier than 1928, though perhaps some clever person will manage to backdate that at some point. References to mixtures of gin, lime, and sugar do seem to date back to the 19th century, so even without the name the drink seems to be at least that old. In any case, the most likely etymology of the drink name, I suspect, is the figurative sense of a penetrating drink. Sorry, Dr. Gimlette.

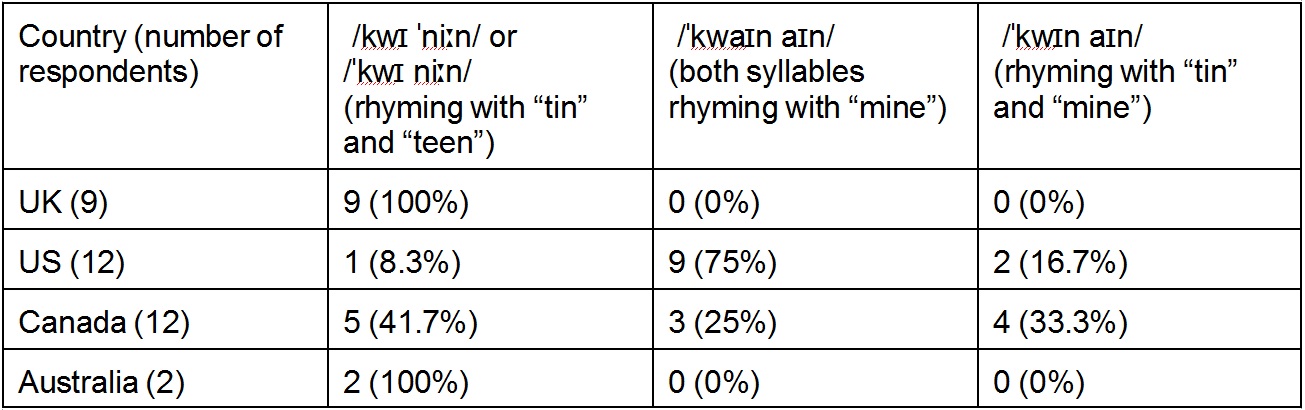

One interesting side detail is the pronunciation of the word quinine. My first instinct was to pronounce it as if to rhyme with "tin" and "mine" (in IPA /ˈkwɪn aɪn/), but I talked myself out of that pronunciation as just mixing up the British and American pronunciations and settled on the British. But after watching a video of quinine fluorescing under UV light that contained a similar uncertainty about the pronunciation, I started to think that my first instinct might represent a particularly Canadian pronunciation. So I polled people I knew on Twitter and Facebook, and here's the result:

Admittedly I don't have a lot of data to go on here, so I'd love to hear from anyone else as to how they pronounce the word, but it does seem clear that the British and American pronunciations are quite consistent (and different from each other), but the Canadian pronunciation is evenly distributed. The American outliers, by the way, are ex-pats living in Europe and Australia, so there may be some influence there. So what do you think?

The botanical name cinchona, by the way, though superficially sounding a bit similar, is not related to quinine and its Quechua root kina, but was instead assigned to the species by Carl Linnaeus, who kind of got the form of the word wrong, in honour of the Spanish Countess of Chinchon who was cured by the bark in 1638 while in Peru in the role of vice-queen, and later brought it back to Spain, after which it became known throughout Europe. This slightly garbled form of the name has nevertheless stuck.

Of course one of the main themes I was trying to draw out here was imperialism and capitalism, with the rise and influence of the East India Companies, in particular with the ongoing rivalry between the British (EIC) and the Dutch (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC). I cheated slightly, in that the word gimlet comes into English from Dutch through Anglo-Normal French, but the number of English borrowings from Dutch later on is significant and historically interesting. The -et on the end of the word is a diminutive suffix in French, so the diminutive form of the word in Dutch would be wimmelkijn. That Dutch suffix comes into English as -kin, as in the word napkin. The point of all this is that though these early commercial efforts led to important innovations like cures for scurvy and malaria (as well as less important innovations like cocktails), they also had the potential for great harm due to European attitudes to colonialism, and at their worst led to devastating atrocities. Our modern world might not be what it is today without this history, but it came with quite a price. For more background on the East India Companies and the rise of the corporation, have a look at this recent article on the British EIC or this Crash Course video on the VOC:

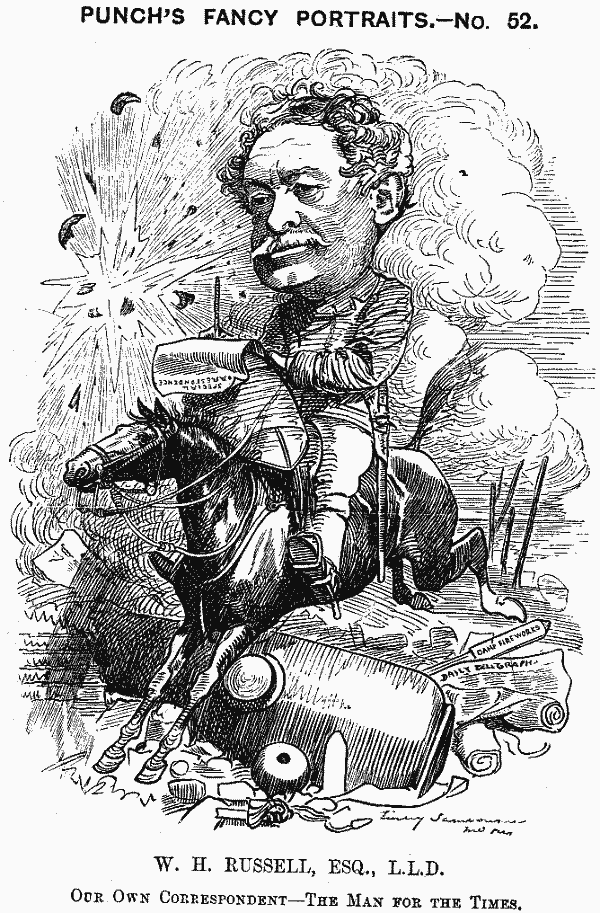

For those tracking previously mentioned links, this time we have the British East India Company, William of Orange, and the Gin Craze, previously mentioned in my first cocktail video. And polymath Erasmus Darwin got a look in in my Coach video. One additional set of links I didn't use in the video has to do with an early advertisement for Rose's Lime Cordial drawn by illustrator Edward Linley Sambourne -- I was unfortunately not able to find an image of this ad online but if you know of one please point it out to me. Sambourne was most famous for being one of the main illustrators for Punch magazine (previously mentioned in "A Detective Story" here) in which he drew a caricature of the first war correspondent William Howard Russell (also previously mentioned in "A Detective Story" here). Sambourne also drew a very famous caricature of Cecil Rhodes, after whom is named Rhodesia and the Rhodes Scholarship which he founded. The deeply racist Rhodes was big into colonialism and was a founder of the massively monopolistic and exploitative De Beers diamond mining company, another fine example of the combination of capitalism and colonialism gone horribly wrong. Sambourne's illustration of him has become iconic of 19th century colonialism.

In the final part of the video, I bring the story of European imperialism around to American imperialism with the story of Smedley Darlington Butler (whom I first heard of, I think, in the excellent Hardcore History podcast). Of course Butler's nickname of Old Gimlet Eye is useful in demonstrating the figurative use of the word gimlet which may also lie behind the name of the cocktail, and makes a nice coincidental parallel with the British naval admiral Old Grogram who invented grog. By the way grog is an example of an eponym, a word which is derived from the name of a person, in this case Old Grogram, and if you believe the Dr. Thomas D. Gimlette etymology for the drink name, that would make it also an eponym. (I discussed the similar concept of the toponym, a word that comes from a place name, in a previous blog post on for the video "Coach".) But Butler's story is also useful in demonstrating the dangers of corporate interests driving colonialist policies in ways not that far removed from the excesses of the British and Dutch East India companies of earlier times. So I'll leave you with Butler's own words, first in an excerpt from an article he wrote in the magazine Common Sense, and then in a video clip of his Business Plot accusation:

I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902–1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.