So writing this post has served a double purpose -- it explains some of the theoretical background to what I want to blog about, especially important if you don’t already have a background in languages or linguistics, but it’s also an opportunity for me to think out loud a bit. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading! As a reward, here’s a sketch by Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie discussing language, which picks up on notions of Saussurian lange and parole, Chomskian generative grammar, the relationship between language and culture, pragmatics, and the formulaic nature of language. See how much funnier it is now that you’ve read all that?21

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hHQ2756cyD8?rel=0&w=420&h=315]

1 Indeed it might actually infuriate you to read this post if you’re an actual linguist, so you may as well stop now. Still here? Okay, but don’t say I didn’t warn you! [back]

2 For instance the Germanic f in English words such as foot, father, and fish corresponds predictably with p in other IE languages, such as Latin pes/pedis, pater, and piscis (and also with Greek πούς and πατηρ, for that matter — feel free to find correspondences in other languages, or consider other basic words like numbers (one, two, three, etc.) in as many languages as you know. It’s fun! [back]

3 An interesting side note, the Danish philologist Rasmus Christian Rask more or less came up with the same idea as Grimm, and Grimm initially credited him with this, hence it’s sometimes referred to as Rask’s-Grimm’s Rule. [back]

4 At least that’s what linguists working in linguistics departments would call it. Today, scholars focusing on language in literary fields, such as my own medieval studies, still tend to use the term philology. [back]

5 Sweet, not known for a sweet disposition but instead something of an irascible figure -- the prefaces to his various works make for quite entertaining reading -- was somewhat embittered that he did not receive a university professorship position as he thought he deserved. I’ve often felt quite a kinship with Sweet, and have often said, though I wouldn’t have wanted to live in the middle ages, I would love to have been a Victorian medieval philologist. [back]

6 This also brings up the distinction between diachronic linguistics, which is another term for historical linguistics (that is the way language changes over time), and synchronic linguistics, the study of language at one point in time. [back]

7 Saussure’s work also kicked off the field of semiotics, which has become significant in the literary critical world. [back]

8 Interestingly, I suspect as many people know of Chomsky for his political commentary as for his linguistics work. I guess politics is more flashy than linguistics. However, in a future post I’d like to explore how politics is really all about language anyway. [back]

9 Chomsky devised the sentence “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously”, demonstrating among other things that the generative grammar can produce a syntactically well-formed sentence even if it was semantically nonsense. Lewis Carroll’s poem “The Jabberwocky” achieves much the same effect. [back]

10 Sapir is known for developing the anthropological approach to linguistics, looking at how language and culture interact, a topic I’m much interested in. As a personal side note, Sapir lived for a time in my hometown Ottawa (Canada), working for the Geological Survey of Canada. That's a connection I'd really like to look more into. [back]

11 Whorf has often been criticised as a dilettante, as he was originally trained as a chemical engineer, and only came to the study of linguistics later in life. However, the strengths and weaknesses of his work should stand for themselves. [back]

12 Essentially the claim is that language can affect the way you think in very fundamental ways; language differences can lead to differences in cognition. The original strong version of this theory, linguistic determinism, claimed that the language you spoke determined the way you were able to think about the world. The more recent versions of this idea claim that language can have an effect on the way you think but is not an absolute determiner of it. You can read more about linguistic relativity on Wikipedia or even better in this easily approachable and very well explained entry by Lera Boroditsky in the Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. [back]

13 Linguistic relativity is a complex topic that I’ve already briefly touched on, and I’ll come back to in more detail in an upcoming post. [back]

14 BEV is now more commonly referred to as African American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Ebonics. For an interesting discussion of this topic, have a listen to episode 4 of Slate’s excellent language podcast Lexicon Valley. [back]

15 A number of medievalists, such as Suzanne Fleischman, Laurel J. Brinton, and Peter Richardson, have focused on pragmatics and discourse markers, and they've been big influences on me as well. I’ll probably write a fuller post on this topic in another post, as pragmatics and discourse markers were the focus of my research for the first five years or so after completing my doctorate. [back]

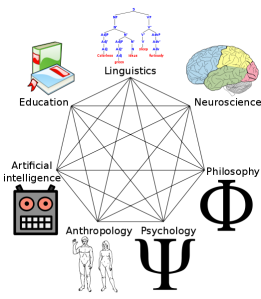

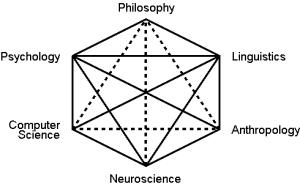

16 This interdisciplinarity is what lies behind the graphics I've included at the beginning and end of this post. The graphics use the hexagram and heptagram to show the interrelated nature of these fields in cognitive science, an image which also lies behind the name of this blog -- the endless knot is a phrase from the 14th century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and refers to the emblem of the pentangle or pentagram which Gawain has emblazoned on his shield. It is an image of the interconnectedness of things. Interconnectivity and interdisciplinarity are at the very heart of what I'm doing, and I'll be blogging much more about them soon. [back]

17 Children learn the basic conceptual schema of “container” when they spend hours putting things in and then taking them out of a box or other container. It seems to fascinate them endlessly to repeat this simple act, which later becomes fundamental to their thinking about the world in later life. [back]

18 Boroditsky’s work has been particularly influential for me lately. I’ve written a bit about this already, and will post a fuller discussion of linguistic relativity later. In the meantime, have a look at Boroditsky’s website, which includes both her scholarly publications and more popular articles, and check out this public lecture, which is a very approachable and entertaining introduction to the subject of linguistic relativity. [back]

19 That certainly is part of what I’m trying to do on this blog. See for instance my post on the seafaring metaphor. [back]

20 Mark Turner has an interesting article along these lines called “The Cognitive Study of Art, Language, and Literature” Poetics Today 23.1 (2002): 9-20. [back]

21 Yes, this whole post has been in part an attempt to show why this sketch is so funny. [back]