Cultures can vary widely in terms of their conceptualisation of time. Simply put, there are many different ways of thinking about time. We can picture time in different ways, drawing on different sets of imagery, or using different metaphors. We can understand time in relation to ourselves or in relation to some external frame of reference. We can divide time up in different ways, and have different beliefs about how time affects us. And how we think about time can be intimately related to a host of broader cultural values or beliefs. In modern western cultures, for instance, we tend to think of time in terms of a three-part structure of past, present, and future, with time moving in one direction without repetition. Though events can repeat themselves, tomorrow is fundamentally different and separate from yesterday.These conceptualisations are not universal across all cultures, and can also change over time. It should also be said that any given culture may have more than one way of looking at time too.

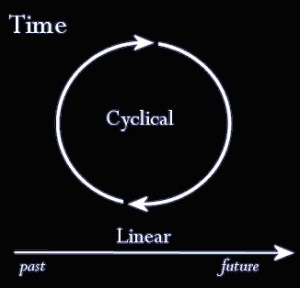

Anthropologists have often described cultures as having either cyclical or linear notions of time. Though this simple binary may be something of an oversimplification, it’s still a useful model to consider. Cyclical time, naturally enough, emphasises repetition and is very much influenced by the cycles apparent in the natural world. The day/night cycle regulates our lives, telling us when to sleep and when it is productive (and safe) to go about the business of agriculture or hunting/gathering. Cyclical patterns are suggested by seasonal cycles and their relation to agriculture. Shorter cyclical patterns, such as the day/night cycle or the phases of the moon, can be used to track these larger cycles, with growing seasons or human gestation lasting so many months or days. In many cultures, these kinds of cyclical patterns are infinitely repeatable and part of a recurring overall cycle of time. Traditionally, anthropologists have identified this notion with early or prehistoric, and I suppose significantly pre-literate, cultures. Without a system of writing, it's hard to envisage a future that is fundamentally different from the past. These types cyclical patterns, of course, haven't gone away from modern western culture, but many argue that they have become subsumed by the larger framework of linear time. Thomas Cahill, for instance, in his book The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels, argues that Judaic culture fundamentally changed Western culture by contributing this sense of linear time, which of course was adopted by Christianity and thus spread throughout Europe and the western world. Here’s an excerpt from the blurb on the website for Cahill’s book:

The Gifts of the Jews reveals the critical change that made western civilization possible. Within the matrix of ancient religions and philosophies, life was seen as part of an endless cycle of birth and death; time was like a wheel, spinning ceaselessly. Yet somehow, the ancient Jews began to see time differently. For them, time had a beginning and an end; it was a narrative, whose triumphant conclusion would come in the future. From this insight came a new conception of men and women as individuals with unique destinies--a conception that would inform the Declaration of Independence--and our hopeful belief in progress and the sense that tomorrow can be better than today. As Thomas Cahill narrates this momentous shift, he also explains the real significance of such Biblical figures as Abraham and Sarah, Moses and the Pharaoh, Joshua, Isaiah, and Jeremiah.

Have a look also at this reading guide to accompany Cahill’s book -- it also gives a useful overview of his argument.

Judeo-Christian thinking implies a one-way, linear time in which the future is fundamentally different from what has gone before, with bibilical time progressing from creation to judgement day. Each successive moment is qualitatively different from the one before, and there is no repetition. According to Cahill this fundamental aspect of modern Western culture comes to us thanks to the Jews, who he argues thought about time in a way that was radically different from all the contemporary cultures in the Mesopotamian world from which they came. And it is not hard to see that our modern sense of progress, of forward momentum, of change, stems from this way of looking at time. Indeed, as Cahill argues, cyclical time is kind of the norm in most cultures around the world, and the Jewish notion of linear time was an unusual innovation when it came along. Having spread, through Christianity, becoming the predominant mindset for modern western culture, it’s influence is global, but we would do well to remember it isn’t universal, and I would argue the same could be said for the handling of time in language.