As it’s Halloween time, the latest video looks at the word “Costume”:

The main point behind this one is the interesting fact that costume and custom are essentially the same word, but came into English through different routes. Furthermore costume/custom show a similar semantic development to the two senses of the word habit. This kicked off the set of associations, but I also explore not only the interesting vocabulary of fashion, but fashion as a communicative language itself. The semiotics of fashion, that is the study of how fashion conveys meaning, is a large and very rich subject, of which I can only barely scratch the surface. Already this video was quite a long one, and there were a lot of interesting bits I had to leave out of the video.

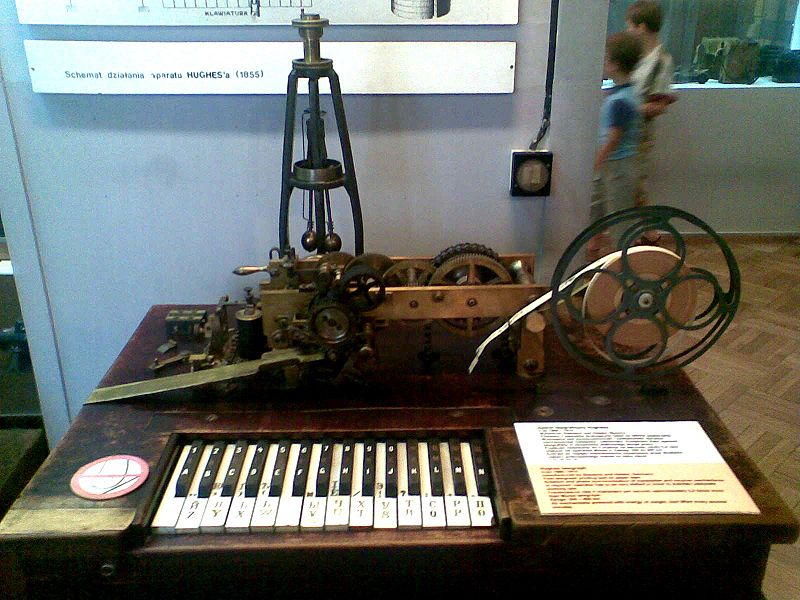

First of all some side notes about the words custom and costume themselves. The plural form customs as in a duty that needs to be paid when importing goods comes from the sense a “customary tax”, and by further extension a customer is someone with whom we have customary business dealings. Costume was first used in English, in the periods of art history sense, by diarist John Evelyn, whom I’ve wanted to include in a video for some time as he’s one of those hyperconnected individuals, and is responsible for coining quite a few words and senses of words, and is just generally a very interesting person.

Now as for Halloween costumes and where we get the tradition of dressing up for this holiday, the ancient Celts in their harvest festival Samhain are said to have dressed up in scary disguises, either to blend in with or scare off other spirits who were believed to arise at that time of year. There’s also the English tradition of souling, going door-to-door in costume around All Souls Day carrying turnip lanterns representing the souls in Purgatory, and offering blessings or songs in return for soul-cakes. Similarly there’s the Scottish and Irish tradition of Guising, going door-to-door in costumes asking for handouts. And then there’s Mumming, an old tradition of costumed dances and little plays performed at various seasons of the year. These various tradition seem to have served two purposes. For one, it relieves the tension from the fear of evil spirits or the souls of the dead. Another is the element of misrule and breaking of taboos which I mentioned in the video. Both of these elements highlight the use of jest and game to lessen the impact of very serious cultural realities. If you’re interested in more about these and other Halloween traditions, I covered many of them in last year’s Halloween video “Jack-o’-Lantern”.

Now getting back to clothing and fashion. One of the sources I looked at suggested that the wimple may have been influenced by or adopted from Muslim women, and thus brought to Europe from the middle east during the crusades. If anyone can provide more information on this I’d be grateful, but there certainly is a similarity between the wimple and the hijab. Sticking with head coverings, I mentioned the 18th century vogue for the wig. An interesting puzzle is the word wig itself. It’s actually short for periwig, which has the earlier forms perwike and peruke, and comes from French perruque and Italian perrucca. But before that the trail runs cold.

On the other hand, I can give some deeper etymologies of some other words mentioned in the video. As I said, jeans comes from Genoa. But where does the name for this Italian city come from? Well there are a couple of theories. First of all the Latin form of the name is Genua. Etymonline suggests it might come from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “curve, bend” and would thus be cognate with Geneva. This root is presumably *genu- meaning “knee, angle”, and also gives us the words knee, kneel, genuflect, and diagonal. Another theory is that it’s related to Latin janua meaning “gate”, and thus also the Roman god Janus, as well as the month name January. As for denim from the city Nîmes, the French placename come from Latin Nemausus and ultimately from the Gaulish word nemo meaning “sanctuary”. This also seems to be connected to a Celtic god which the Romans referred to as Deus Nemausus, the god of a healing-spring sanctuary in the ancient town there. So if you think you look divine in those jeans, what with Nemausus and Janus, you may be right!

And speaking of jeans, I refer to them as an icon of contemporary fashion, probably the 20th century’s most enduring one. But to complete the look I suppose we could include T-shirts and sneakers. So as for the T-shirt, obviously named for its shape, it was originally designed as an undershirt to go with US military uniforms, but many servicemen began wearing just their T-shirts with their uniform trousers as a casual outfit during their off-duty hours, and when film star Marlon Brando appeared in the movie A Streetcar Named Desire dressed in a T-shirt, a fashion style was born. And next the sneaker, an early example of which is the Converse All-Stars, which was also one of the first instances of a celebrity endorsement when basketball star Chuck Taylor joined their sales force in 1921, suggesting improvements to their shoe design, and his signature was added to the ankle patch on the shoes we now often refer to as Chuck Taylors or simply Chucks. The term sneaker by the way dates from the end of 19th century and is originally American, though it’s predated slightly by the term sneak. There are of course many other names for different varieties of casual soft-soled shoe including running shoes, trainers, sand shoes, deck shoes, tennis shoes, and plimsolls, an eponym from politician Samuel Plimsoll who devised the plimsoll line, the water line markings on the side of a ship which showed the maximum load a ship could safely carry — the shoes took their name from the similarity of their appearance to ships with these lines on the side. And as for celebrity endorsements, they have since become quite the big deal with sneakers, and T-shirts have become an important canvas on which to display a variety of messages the wearer wishes to convey to the world, so again fashion as language.

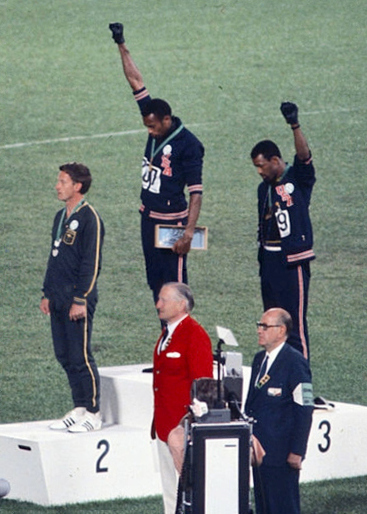

In addition to T-shirts with political or social slogans (which became particularly popular starting in the 1980s), fashion can often be used to make political or social statements. To give just two such examples of statements calling for change, at the 1968 Olympics African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos held up black-gloved fists during their medal ceremonies as an anti-racism statement. And the name of 19th century feminist Amelia Bloomer, who advocated against the restrictive clothing women were forced to wear at the time, became associated with bloomers, a kind of loose fitting split-leg garment, sometimes worn as more comfortable underwear and sometimes as trousers. Once again, the language of fashion and fashion as language. Let me know of any other examples of this kind of use of fashion in the comments below.

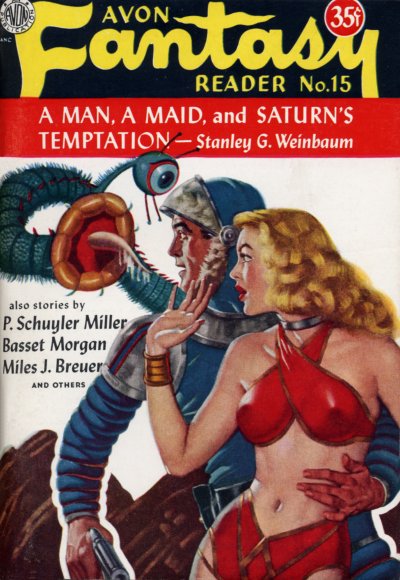

But getting back to the 20th century US military influence on fashion, one perhaps surprising example is the bikini, which inventor Louis Réard named after the Bikini Atoll where the US military conducted its first peace-time nuclear weapons test. Réard hoped his invention would cause a similar "explosive commercial and cultural reaction", and indeed it did. The placename Bikini, by the way is Marshallese for “coconut place”.

In the video I mentioned Beau Brummell’s influence on the men’s formal suit. Brummell was fond of wearing dark colours as opposed to the more brightly coloured outfits of preceding generations. But we have another historical figure, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who by the way gave us the cliche novel opening “It was a dark and stormy night” (you may remember him from our “Beef” video), to thank for the habit of wearing black as formal wear, as in the tailcoat and the tuxedo. As for the invention of tuxedo itself, one story goes that Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, wanting a more comfortable formal outfit than the black tailcoat, took to wearing a short military style jacket. His American guest at the time, James Potter, brought the style back with him, and after wearing it at the fashionable resort of Tuxedo Park in New York, a style and its name were born. The place name itself, by the way, seems to come from Algonquian p'tuck-sepo meaning “crooked river”. On the subject of the tuxedo, the term Canadian tuxedo refers to wearing denim on top and on bottom, so jeans and a jean jacket for instance. And the term Canadian passport, according to Urban Dictionary, is another term for the mullet cut. I don’t want to think what all this implies about Canadians!

But while we’re still on the subject of men’s formal wear, the top hat is said to have been invented by John Hetherington, who supposedly first wore this shiny silk hat designed to “frighten timid people” on January 15, 1797, causing a riot with women fainting, children screaming, and dogs yelping, leading to his being charged with a breach of the peace! Unfortunately this story may be apocryphal. Nevertheless, the hat did become a major fashion trend of the 19th century, and already by 1814 we have the first recorded instance of someone pulling a rabbit out of a top hat, the French magician Louis Comte.

Another probably apocryphal hat story is about the invention of the bowler. Finding the tall top hat inconvenient when horse riding as it got caught up in low-hanging tree branches, wealthy British landowner William Coke commissioned a hat with a low round crown. The hat was manufactured by one William Bowlers. Of course it might just be the bowl shape of the hat that led to its name. But I’ll make the hat trick by relaying a third hat story. The fedora takes its name from a play, the only such instance of an etymology I can think of. In the play Fedora by Victorien Sardou, famous actress Sarah Bernhardt wore a soft felt hat while playing the title role of Princess Fedora Romanoff, and the hat became a popular fashion choice.

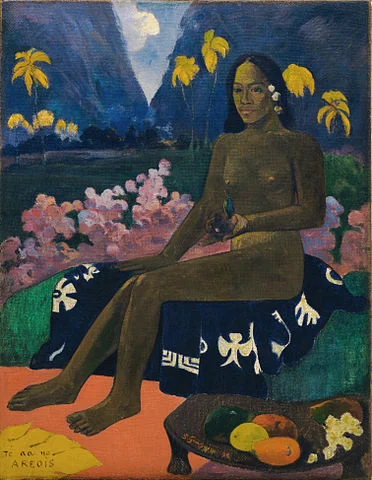

Speaking of fashion trendsetters, I mentioned Empress Josephine’s role in popularizing the empire waist dress, a neoclassical reinvention of the ancient Greek peplos. Another important trendsetter in the development of this type of dress was Emma, Lady Hamilton (or Emma Hart as she was known at the time), who was the lover of Charles Greville (whom you may remember as a friend of Erasmus Darwin in our previous video on him). Greville, tiring of his mistress, shipped her off to Italy to become the mistress and eventually wife of Sir William Hamilton, who was the English ambassador in Naples. While there Emma invented a kind of performance art she called Attitudes, posing in various alluring poses recreating scenes from Greek mythology, and wearing that type of ancient dress. The artist George Romney painted many of these scenes, and her fashion sense took Europe by storm. Well, I guess high fashion is all about attitude.

Speaking of ancient Greece, professional barbers or hair cutters go back at least as far as ancient Greece, where the barbershop was already an important location for conversation and gossip. The Greeks introduced the profession to the Romans who called the barber a tonsor, related to our word tonsure. During the middle ages barbers also served as surgeons — after all they already had sharp razors — and that’s the source of the barber pole, the red stripes reflecting the blood involved. The word surgery by the way comes through Latin chirurgia ultimately from ancient Greek kheirurgia meaning literally “hand work”. So some extra tidbits next time you’re gossipping with your barber.

Also in the ancient world, I briefly mention the toga, which connects nicely with our last video “Ambition” and the toga candida, the “whitened toga”, worn by political candidates in Rome, and indeed that’s where the word candidate comes from. Also worthy of mention is the toga praetexta, which had a purple border, and was worn, curiously, by both by young boys who were not yet of age and by magistrates, purple being a colour that signified high status, but more on this when we come to purple in our ongoing series of colour podcasts. Interesting too that the one exception to the rule that only freeborn males were allowed to wear togas was that prostitutes were required to wear them, an example I suppose of boundary crossing. They couldn’t wear the traditional stola, the dress of the Roman matron, and I suppose had something of the male freedom in terms of their status—in the sense that they were not restricted by the modesty of a respectable woman. The toga, though, showed that they also lacked the legal protection of a citizen woman, and that their bodies were essentially common property.

In the video I highlighted the importance of France as the home of fashion by tracing the series of leaders from Louis XIV and his wigs, to Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour, to Louis XVI and his wife and “queen of fashion” Marie Antoinette, leading up to the French Revolution, to finally the more reserved styles after the revolution with Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. I could perhaps add one other link to this chain, with Napoleon’s nephew and heir Napoleon III and his wife Eugénie de Montijo. She influence the work of designer Charles Worth, who is known as the father of haute-couture, and who founded the first great fashion house, the House of Worth.

And finally one last point about fashion as language. A friend once pointed out to me that someone mixing clashing styles of clothing was engaging in something like code-switching. Code-switching is a linguistics term that refers to when speakers of more than one language naturally switch back and forth between languages in the middle of conversation. It’s not a random phenomenon, but is indeed itself a communicative element of language — the choice of language at any one instant communicates something of importance in the discourse. Applying this to clothing is, I think, quite relevant, particularly in our modern, uncentred contemporary fashions. So feel free to add in the comments any other ways fashion is like language — I’d love to hear some other views.