This week's video explores the etymology of the word "clue", from Greek myth to detective fiction:

The idea for this one obviously came from the narrative metaphor of the Ariadne story leading to current meaning of the word clue, and the interesting references in Agatha Christie's writings to Greek myth made for a nice closed loop. The story of the development of fingerprinting, with the nice visual analogy between the contours of a fingerprint and the labyrinth of the Minotaur, became the centrepiece, and looking backward from clew "ball of thread" to the Proto-Indo-European root *gel-, leading also to clay and glia, gave some additional connections. I've already touched on the importance of narrative and metaphor, and for that matter on detective fiction, and Sherlock Holmes specifically, in "The Story of Narrative", "Paddle Your Own Canoe", and "A Detective Story" respectively, so in a sense this video is a culmination of that initial series of videos. Oh, and speaking of sailing technology in "Paddle Your Own Canoe", another meaning for the word clew is the bottom corner of a sail. And while I'm on the subject of links to previous videos, Chaucer has come up before, not only in "Paddle Your Own Canoe" but also "Cuckold", and Erasmus Darwin in "Coach" and "Gimlet". The illustrious Darwin-Wedgwood family will no doubt come up again.

And speaking of Geoffrey Chaucer, I should stress his importance along with other medieval and early modern writers for associating the word clew with the Theseus and Ariadne story. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the passage quoted in the video as the earliest with specific reference to the Labyrinth story. The passage is from Chaucer's The Legend of Good Women, which recounts the stories of various virtuous women, several of them drawn from Greek myth. I mentioned some of the most obvious reference to weaving and other textile arts in Greek myth, the Fates, Penelope, & Ariadne, but it should also be noted that Athene herself, who appears in the story of Theseus leading him away from Ariadne, and in The Odyssey helping Odysseus as he arrives home to Penelope, is also particularly associated with weaving. For instance, there is the story of Arachne, a talented weaver who wins a weaving contest against Athene, and as punishment is transformed into a spider (hence "arachnids" as a term for spiders). Athene is the goddess of wisdom, which for men expresses itself as strategy -- she was thus a goddess of that side of warfare as opposed to Ares who represented the bloodlust of war -- and for women expresses itself as weaving and other domestic arts. A double standard that reflects Greek patriarchy, but it shouldn't be forgotten that wisdom is being anthropomorphised as female, with her mother Metis also being associated with wisdom. There is indeed a thread of clever and cunning women running through Greek myths. Penelope is an ideal match for the cunning Odysseus (who was for instance the one who came up with the Trojan horse idea) because she too is clever, tricking the suitors to keep them at bay until Odysseus returns home.

Another interesting instance of weaving in Greek myth is the story of Procne and Philomela. As the story goes, when Philomela was visiting her sister Procne, her brother-in-law Tereus raped her, and in order to conceal the attack he cut out her tongue. Philomela, however, was able to communicate the crime by weaving it into a tapestry, and the two sisters are able to exact their revenge. Chaucer also includes this story in The Legend of Good Women. An interesting modern parallel to the idea of communication through textiles is the idea of knitting in code. During the Second World War, the British government banned the sending of knitting patterns out of the country for fear that they might contain coded messages, and in Belgium the resistance recorded the movement of trains in their knitting. And in a more literary example, Charles Dickens wrote of the macabre Madame Defarge in A Tale of Two Cities, who sat by the guillotine recording the beheadings in her knitting. (See here and here for this and these and other knitting trivia from QI). An often repeated though unfortunately apocryphal story is that Irish knitters used the intricate patterns of Aran sweaters to identify the bodies of men drowned at sea. The story seems to have grown out of a passage in the play Riders to the Sea by the Irish playwright J.M. Synge, where a drowned man is identified not by a knitted sweater but by his knitted stocking: "It's the second one of the third pair I knitted, and I put up three-score stitches, and I dropped four of them." (See here and here for more details.) Too bad too, because that story would make a nice parallel to the use of fingerprints for identification, tying clew and clue together again.

So back to fingerprints; the original motivation for the fingerprinting system in the 19th century was not so much detection but for identification of repeat offenders, who were supposed to receive harsher penalties. As a result of increased population and greater mobility throughout the country due to the industrial revolution, while it used to be the case that local repeat offenders would be quickly recognized, repeat offenders who moved around a lot were much harder to track. Before fingerprinting was settled on, a number of other systems of identification were mooted, most significantly anthropometry, a the detailed measurement of a person's physical characteristics similar to what we now call biometrics. A system for this was worked out by the French policeman Alphonse Bertillon, unsurprisingly attracting the attention of Francis Galton, who was interested in quantifying human heredity through both physical and mental characteristics. Edward Henry had also been using Bertillon's system in India, until Galton's book was forwarded to him. And speaking of Bertillon, he and his system are referenced twice in the Sherlock Holmes canon, in "The Naval Treaty" and The Hound of the Baskervilles, as being admired by Holmes, who is himself referred to as the "second highest expert in Europe" behind only Bertillon. And in a fictional crossover going the other way, Edmond Locard of Locard's Exchange Principle fame was known as the Sherlock Holmes of France. And of course, as is well known, the character of Sherlock Holmes is based on the real-life Dr Joseph Bell, a former medical school teacher of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was himself a pioneer of forensic science.

As for Francis Galton, the archetypal 19th century gentleman-scientist, though it should be noted that Galton himself was not directly related to Josiah Wedgwood (Wedgwood was Charles Darwin's grandfather on the other side of the family -- Erasmus Darwin was their common grandfather), the whole Darwin-Wedgwood clan was full of illustrious go-getters. Galton's other grandfather, Samuel Galton, was a founding member of the Lunar Society (previously mentioned here), along with Erasmus Darwin, as well as Joseph Priestly (previously mentioned here), in whose former house Galton was born. The Darwin-Wedgwood family also later includes the likes of composer Ralph Vaughn Williams and Anglo-Saxonist Simon Keynes (a connection of particular interest to me as an Anglo-Saxonist myself). In addition to his important work on fingerprints and statistics, and his rather more questionable work on the pseudoscience of eugenics and that crazy beauty map of Britain, he is also significant for his pioneering of the science of meteorology. You can read more about him and his contributions to science in this article. One last bit of trivia about him: he worked out through careful study the ideal procedure for brewing tea, which you can read below, take from the excellent website galton.org, which has collected works available online:

Edward Morse is another fascinating Victorian polymath. In addition to his important work as a naturalist studying shells, as noted in the video he made pioneering contributions to the study of Japanese pottery, particularly the cord-marked pottery of the Jomon period (pictured in the video) which dates as far back as 16,000 years ago. He also wrote the book Japanese Homes and their Surroundings, which described the construction and furnishings of Japanese houses, including sections on bonsai and flower arrangement, and as a result of his friendship with astronomer Percival Lowell he wrote Mars and Its Mystery about the possibility of life on Mars.

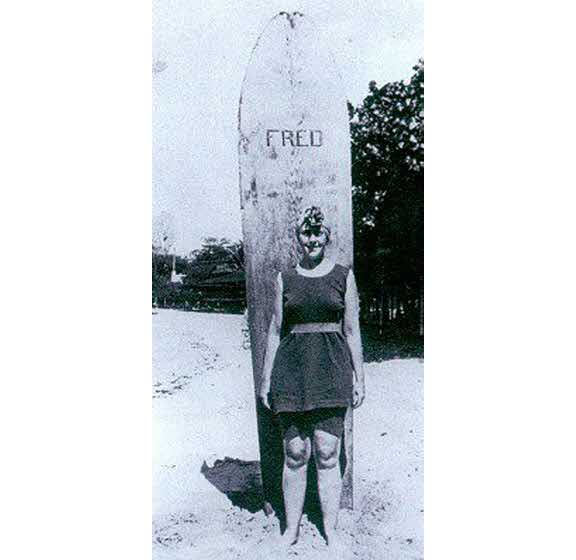

I'll leave you with one last bit of trivia, concerning Agatha Christie. Reasonably well known is Christie's disappearance for a little over a week during the break-up of her marriage (the subject of a Doctor Who episode no less). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, surprisingly a proponent of the occult, even enlisted the help of a spiritualist to assist in locating her. But perhaps less well known is that she was one of the first Brits to surf standing up, a pastime she took up while on holiday with said former husband. Here she is with her surf board, apparently named Fred: