This week's video is about the history of the word "fossil", and the study of fossils from the ancient world to the 19th century:

The basic theme of this one is, of course, the importance of Latin and Greek to scientific terminology, and beyond that the larger debt science owes to the classical world, as for instance with the Latin-derived words fossil and strata themselves, the many scientific names for organisms drawn from Latin and Greek, and the metaphorical reference to the Roman gods Neptune, Pluto, and Vulcan in the geological terms neptunism, plutonism, and vulcanism. It made a convenient starting point, therefore, to mention the reception of fossils themselves in the ancient world, for which I drew on the research of Adrienne Mayor -- she gives a fuller treatment of this in her book The First Fossil Hunters. On the subject of sources, for the later history of geology and palaeontology, I've drawn on Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything, James Burke's The Day the Universe Changed episode 8 “Fit to Rule: Darwin’s Revolution” and the corresponding chapter in his book of the same name, and the excellent website Strange Science: the Rocky Road to Modern Paleontology and Biology. As always, a fuller list of sources can be found on the show notes page. The etymological trigger for this story is the fact that fossil and bed come from the same Proto-Indo-European root word, and this tied in nicely to the additional etymology focussed on in this video "strata", which in addition to its geological sense in English, could in Latin refer to a bed cover, and this further tied into the recent find of the earliest known bed, itself a demonstration of the principles of stratigraphy. I also took the opportunity to tie in another recent development, the recent revival of the name Brontosaurus, and I suppose I could have mentioned recent work on analysis of the mammoth genome.

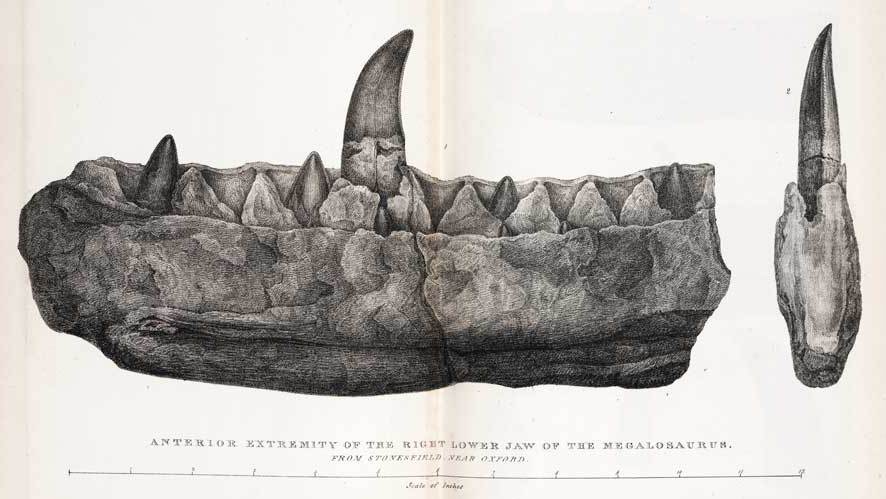

There are of course many details I had to leave out, especially since my main goal was to tell the story of the linguistic and classical backgrounds to the study of fossils (so do check out main sources I listed above for a fuller story). For instance, there's the 17th century scientist Nicolas Steno who proposed the Law of Superposition, that each stratum was newer than the one below it. And the Comte de Buffon, only briefly mentioned, was also very significant for being one of the first to really argue for an age of the earth much longer than the Bible accounted for (though he was still orders of magnitude under). Or the evolutionary debate between Charles Darwin's natural selection and Lamarckism, proposed by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, that suggested new characteristics developed during an organism's lifetime could be passed on to its offspring. Bone Wars enemies Cope and Marsh were on opposite sides of this debate, and though Darwin's model obviously won the day, interestingly Lamarckism presaged resent research into epigenetics. And it was Thomas Henry Huxley, nickname Darwin's Bulldog for his fierce defense of Darwin's theory, who was particularly concerned with bird evolution from dinosaurs, was the conduit between O.C. Marsh and Darwin. But aside from this scattershot list, there are few additional elements I want to mention here in a little more detail.

It's notable how important dining clubs were to the progress of science in the 18th and 19th centuries. I mentioned the Oyster Club in the video, important for transmitting Hutton's work via John Playfair (whose brother William, by the way, invented the line graph, the bar chart, and the pie chart), and in my previous video "Gimlet" I mentioned the Lunar Society, of which Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) was a founding member. And speaking of Erasmus Darwin, by the way, he wrote a long poetic adaptation of the plant classification system of Carl Linnaeus (which you can read here if you wish). And in the Gimlet blog post I mentioned how Linnaeus mishandled the botanical name of the cinchona tree, the source of quinine, so there's another circular connection for you! Worth adding to the list here then is the Poker Club, also central to the Scottish Enlightenment, and the X Club, whose members were all supporters of Darwin's natural selection and which was founded by Huxley. No doubt the dining club scene will crop up again.

But this also highlights the fact that men of a certain class and standing were at the centre of scientific progress, for the simple reason that they had education and the leisure time to devote to such work, and the efforts of those of lower class or of women were often side-lined. For instance, William "Strata" Smith, due to his lower class background and education, was often dismissed or even screwed over by the geological in-crowd, in particular by one George Bellas Greenborough who plagiarised and then undercut the selling price of his map. Eventually Smith spent time in a debter’s prison, only later in life receiving real recognition for his work. And the work of fossil hunter Mary Anning was often downplayed by the scientific community, though she is particularly important to this story for putting William Buckland onto coprolites (as well as for her role in the discovery of the Ichthyosaur, meaning "fish-lizard", a marine reptile, not to be confused with Marsh's Ichthyornis, the toothed bird).

And it's with Buckland that I most want to add some details, but not William Buckland, but his wife Mary Buckland née Morland. Mary and William shared an interest in palaeontology and geology. The story goes that they met in a coach in Dorset while both were reading the same book by Georges Cuvier. They struck up a conversation and one thing led to another. As Mary and William's daughter Elizabeth Oke Buckland Gordon records in her biography of her father:

Dr. Buckland was once travelling somewhere in Dorsetshire, and reading a new and weighty book of Cuvier's which he had just received from the publisher ; a lady was also in the coach, and amongst her books was this identical one, which Cuvier had sent her. They got into conversation, the drift of which was so peculiar that Dr. Buckland at last exclaimed, "You must be Miss Morland, to whom I am about to deliver a letter of introduction." He was right, and she soon became Mrs. Buckland. She is an admirable fossil geologist, and makes models in leather of some of the rare discoveries.

Mary was herself an avid fossil hunter and a notable scientific illustrator in her own right, producing drawings for Georges Cuvier, William Conybeare, as well as her husband, and was as keenly interested in the sciences of geology and palaeontology as William:

Mary Morland, whose mother died when she was only an infant, was the eldest of a large family of half-brothers and sisters. The greater part of her childhood was spent at Oxford, where she resided with the famous physician Sir Christopher Pegge, whose childless wife took great delight in the lovable and intelligent child. In the University City, and, perhaps, through her acquaintance with the learned Professor of Mineralogy, she acquired that love of natural science which was such a joy to her through all her life. Within a few hours of her death she was working at the microscope, ever looking expectantly for a clearer light in the next world to be shed on the wonders learnt here. Sir R. Murchison, writing of the happy union between Buckland and his wife, calls Mrs. Buckland " a truly excellent and intellectual woman, who, aiding her husband in several of his most difficult researches, has laboured well in her vocation to render her children worthy of their father's name.

Indeed their honeymoon was a year-long geological tour, and Mary often helped William with his research and writings, which he dictated to her and she edited, and famously assisted with an experiment involving a flour paste and the family's pet tortoise to identify fossilized footprints. She was also William's curator, mending fossils and making models. So her own contributions to this story should not be underestimated (you can read her Wikipedia entry here or her biography in the ODNB here). One of their children, Frank Buckland, became a celebrated naturalist in his own right, purportedly able to identify fossils as a child, and also inherited his father's habit of zoophagy, eating his way through the animal kingdom. So a notable and interesting family all around. Here's Frank's account of his mother (quoted from here) and a family silhouette:

Not only was she a pious, amiable, and excellent helpmate to my father; but being naturally endowed with great mental powers, habits of perseverance and order, tempered by excellent judgement, she materially assisted her husband in his literary labours, and often gave to them a polish which added not a little to their merit … Not only with her pen did she render material assistance, but her natural talent in the use of her pencil enabled her to give accurate illustrations and finished drawings … She was also particularly clever and neat in mending broken fossils … It was her occupation also to label the specimens.

But getting back to the word "fossil", there was in fact an earlier 16th c. use of the word in English to refer to fish, not as the petrified remains of fish, but living fish that were thought to live in underground water. Here's the first citation of this sense, and later one that clarifies what's being described: "The auncient Philosophers affirme, that there haue bene founde fishes vnder the earth, who (for that cause) they called Focilles"; "Where these Fossil fishes are found, there are subterraneall waters not farre off, by which they are conveyed thither." A curious belief that there were underground bodies of water populated by fish. And of course there's the figurative use of the word to refer to a person or thing that is out of date, first used by Ralph Waldo Emerson: "Government has been a fossil; it should be a plant." And here are a couple of other literary uses of this metaphor too interesting to leave out: "When a man endures patiently what ought to be unendurable, he is a fossil" (C. Brontë, The Professor); "The working or serving man, shall be a buried by-gone, a superseded fossil" (H. Melville, The Confidence-Man). So I suppose older scientists with outmoded ideas become fossils themselves!

There's another nice set of connections I didn't mention in the video, and it starts with the etymology for the word volcano. Volcano comes into English in the early 17th century from Italian. The word, as I said, comes from the name of the Roman god Vulcan, as it was believed that this god of fire and metalworking resided in Mount Etna, and as chance would have it, it was the study of Etna that afforded Charles Lyell the evidence of fossil shells in strata that ran under the mountain, which allowed him to estimate the great age and slow process of both geology and the fossilized remains. Fitting then that it was Vulcan's abode! Interesting, too, that the name Vulcan is itself not Latin in origin, but possibly borrowed from Etruscan, or connected to the Minoan Welkhanoc, ultimately from Hittite Valhannasses. But back to Lyell; though friends with Charles Darwin, he didn't immediately fully accept his friend's theory, and also proposed the idea that geological and biological history might be cyclical, and earlier forms of life might return, a notion ridiculed by fellow scientist Henry De la Beche in a cartoon called "Awful Changes", in which Lyell is depicted as a lecturing Ichthyosaur:

It's significant that he's an Ichthyosaur, as De la Beche was a close friend of Mary Anning (remember her role in the discovery of the Ichthyosaur), and De la Beche also produced a picture titled "Duria Antiquior" of Anning's various discoveries -- the proceeds from the prints to benefit Anning who was having financial difficulties -- which came to be one of the first popular artistic depictions of ancient life:

And as a final amusing sidenote for De la Beche, he once took the role of test-vomiter in the investigation of overflowing privies conducted by Lyon Playfair, whom I've previously mentioned as the being the first to propose the use of chemical warfare.

There's one last footnote to this story, in relation to the story of Thomas Jefferson's mammoth cheese. Jefferson was another of these 19th century polymaths, and in addition to his interests in natural science and palaeontology, he was also linguistically talented -- in addition to Latin and Greek, as well as several modern European languages, he studied Anglo-Saxon and even wrote an essay on the teaching of the Anglo-Saxon language -- so he would probably have been quite interested in both the linguistic and scientific elements of this video. The mammoth cheese in question was made in Cheshire, Massachusetts and presented to Jefferson in recognition of his stance on religious tolerance.

The mammoth cheese was kept in the White House for a couple of years until a mammoth loaf, this time made by the US Navy to rally support for the war against the Barbary States, was similarly presented to Jefferson to accompany it (and you can watch my earlier video on the word 'loaf' and the metaphorical implications of bread here). Apparently this kicked off something of a tradition of mammoth cheeses, with later president Andrew Jackson also receiving a giant cheese:

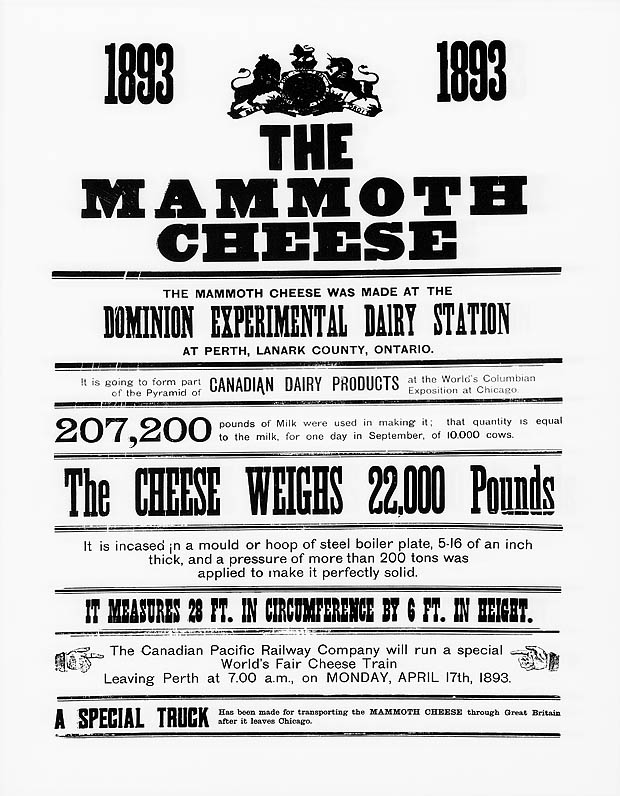

And so the making of mammoth cheeses became something of a tradition, even here in my home country Canada (see here for a brief write up), and one such giant cheese even inspired James McIntyre to write "Ode on the Mammoth Cheese", regarded as the worst ever poem in Canadian literary history; this distinction notwithstanding, the poem is celebrated by an annual cheese poetry competition in his hometown of Ingersoll, Ontario.

Ode on the Mammoth Cheese

We have seen the Queen of cheese,

Laying quietly at your ease,

Gently fanned by evening breeze --

Thy fair form no flies dare seize.

All gaily dressed soon you'll go

To the great Provincial Show,

To be admired by many a beau

In the city of Toronto.

Cows numerous as a swarm of bees --

Or as the leaves upon the trees --

It did require to make thee please,

And stand unrivalled Queen of Cheese.

May you not receive a scar as

We have heard that Mr. Harris

Intends to send you off as far as

The great World's show at Paris.

Of the youth -- beware of these --

For some of them might rudely squeeze

And bite your cheek; then songs or glees

We could not sing o' Queen of Cheese.

We'rt thou suspended from baloon,

You'd cast a shade, even at noon;

Folks would think it was the moon

About to fall and crush them soon.